MIGA (Musashino Institute for Global Affairs)

GSRC (Global South Research Caucus)

November 2024

MIGA policy package “Path Diversity” for “No One Left Behind”

- 1. Outline

- 2. Outline of the workshop

- 3. Background of the Report

- 4. Summary of the Report

- 5. Future Activities and Major Schedules

- Summary and full text of each chapter of the Report

- Chapter 1 MIGA Policy Package

- The Path Diversity Paradigm of the Development of the Global South

- [Special Article 1] International Trade Order

- [Special Article 2] G20-T20 Process: Can Global South Shift the World Order?

- 1. Washington Consensus on Global Economic Governance, shortfalls and Emergence of G20

- 2. New Global Consensus on Development and Evolution of Global South within G20

- 3. The Troika Global South Presidencies in G20 for Building Consensus on New Global Governance Mechanisms

- 4. Participation of Academia and Non-State Actors a in setting G20 Agenda Settings on Global Governance

- 5. Global South’s Challenge in G20 in Building Alternative to the Washington Consensus

- 6. Conclusion

- Chapter 2 Global Environmental Issues

- Policy RecommendationsⅠ Global Warming Issues

- Policy Recommendations II Energy

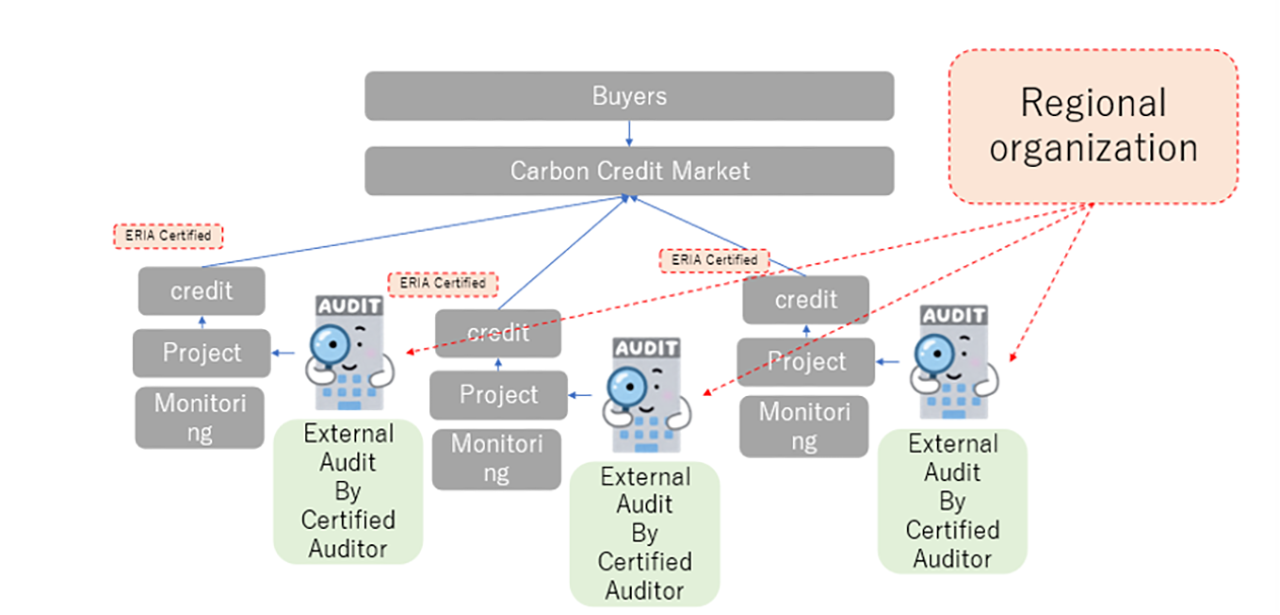

- Policy Recommendations III Expanding the Carbon Credit Voluntary Market

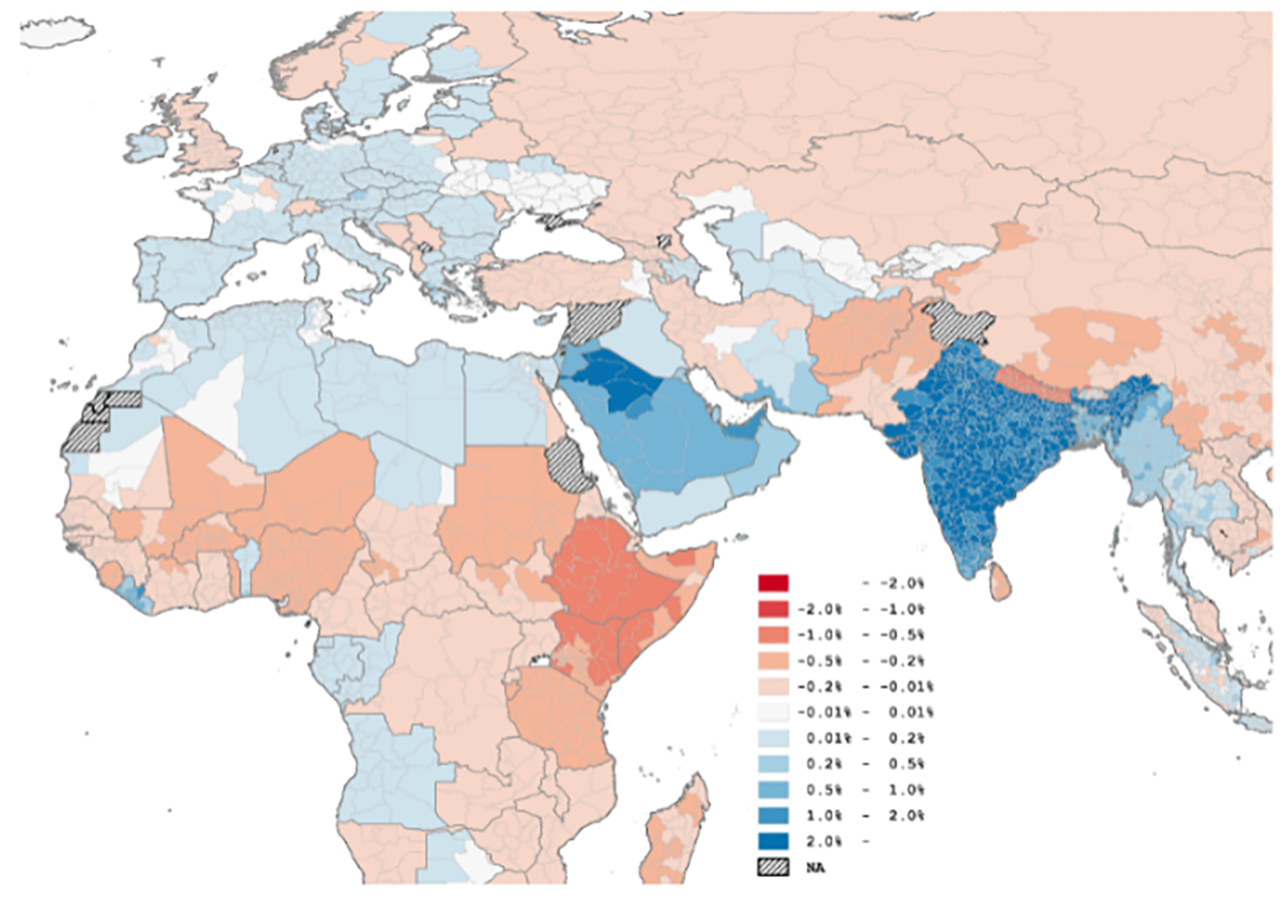

- Policy RecommendationsⅣ The Role of Agglomeration on Diverse Paths to Sustainable Development

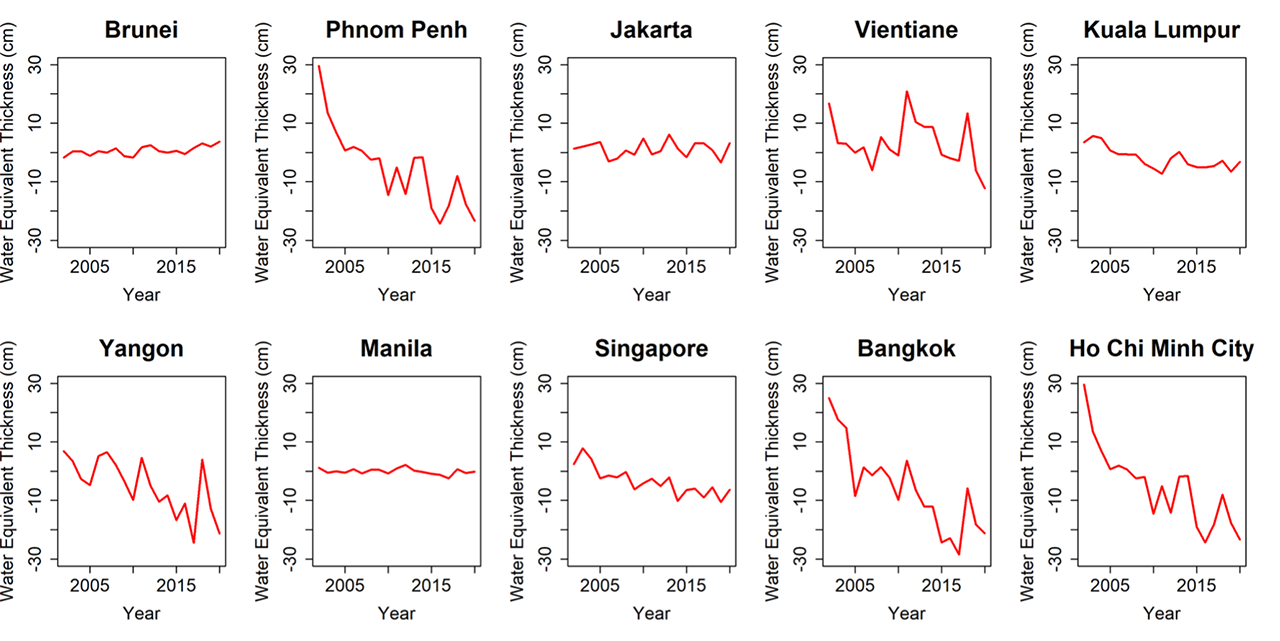

- Policy RecommendationsⅤ the Watershed Ecosystem-Enhancing Urban Development

- Chapter 3 Development Strategies

- Policy RecommendationsⅥ ”Leapfrog” Development Strategy

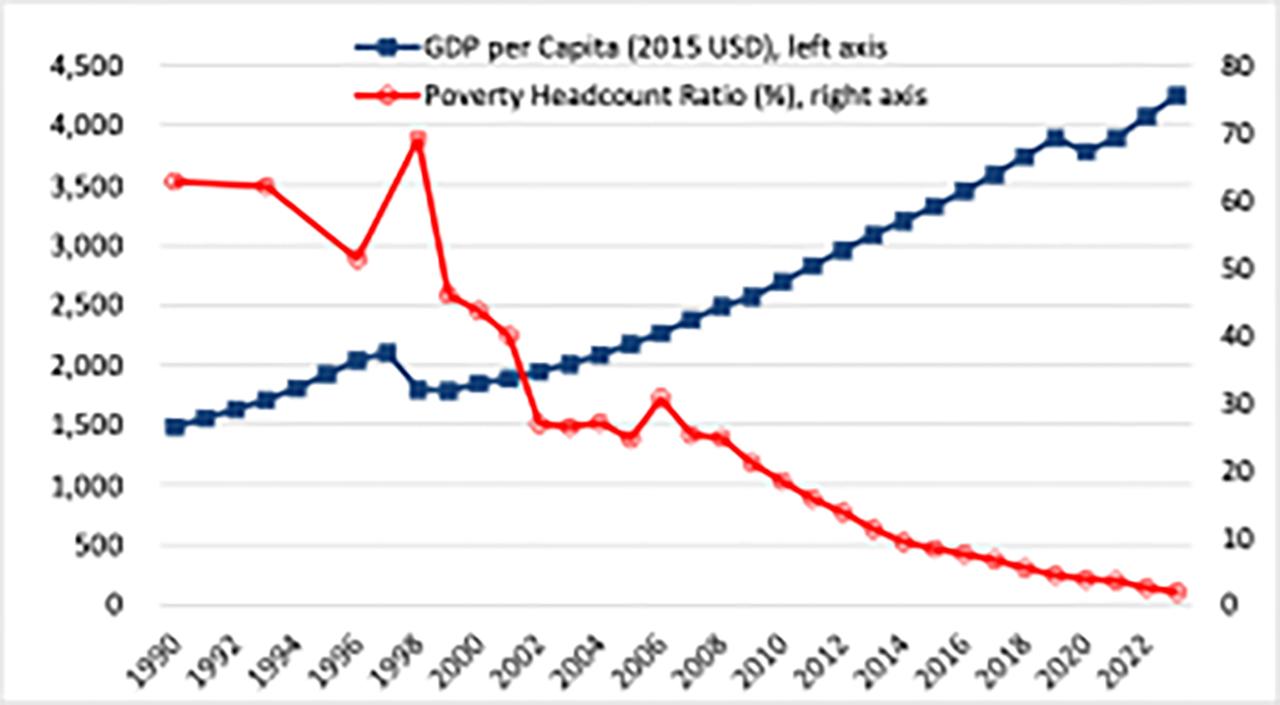

- 1. The Global Common Targets: Sustainable Economic Growth in the Global South

- 2. The Traditional Western Led Path: Following the “East Asian Success Story”

- 3. The Global South Diversity Path: Leapfrogging Economic Development Strategy Based on Digital Technology

- 4. Policies to achieve the Global South Diversity Path:

- Policy RecommendationsⅦ Creation of a New International Development Finance System

- Policy RecommendationsⅥ ”Leapfrog” Development Strategy

- Chapter 4 Social Sector

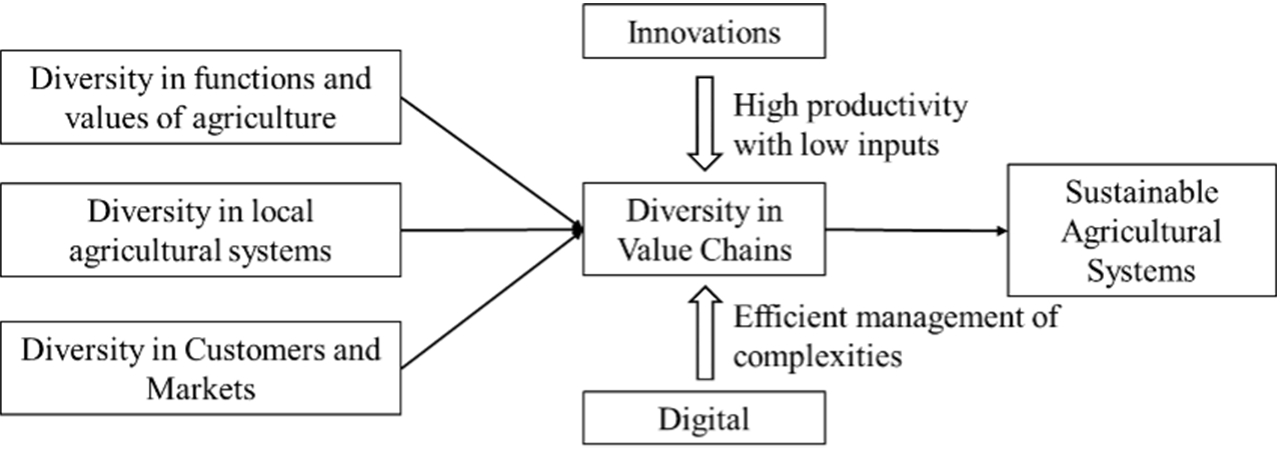

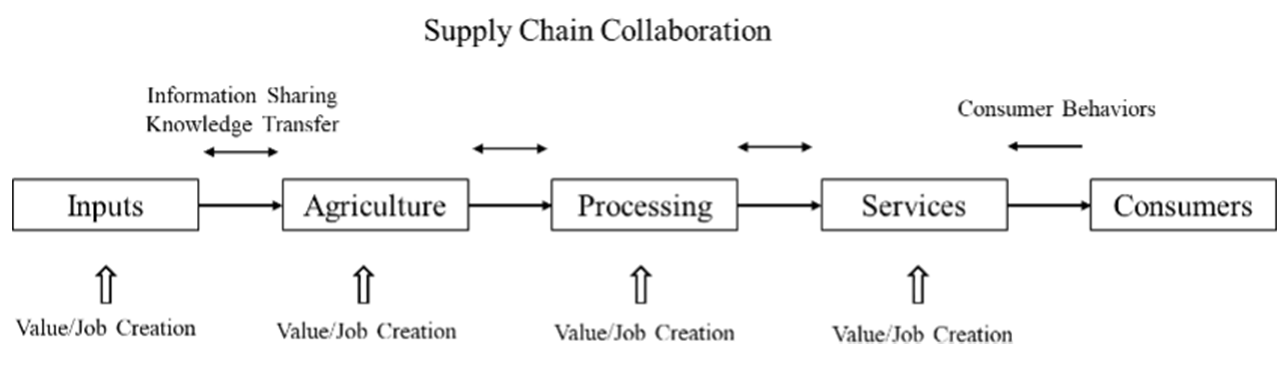

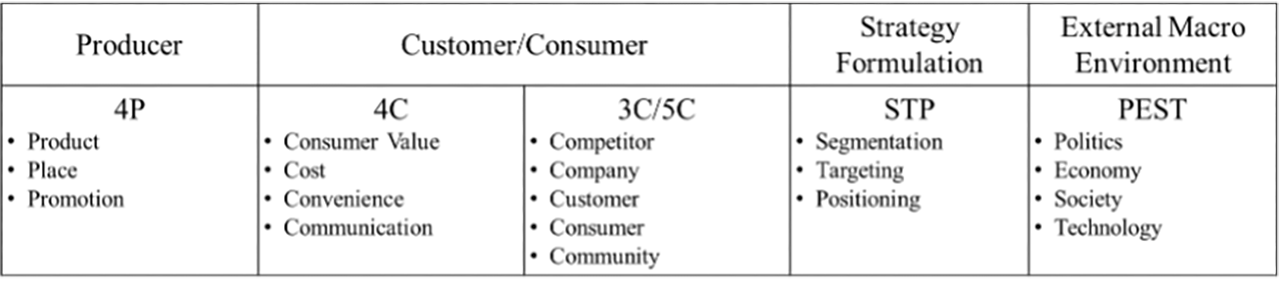

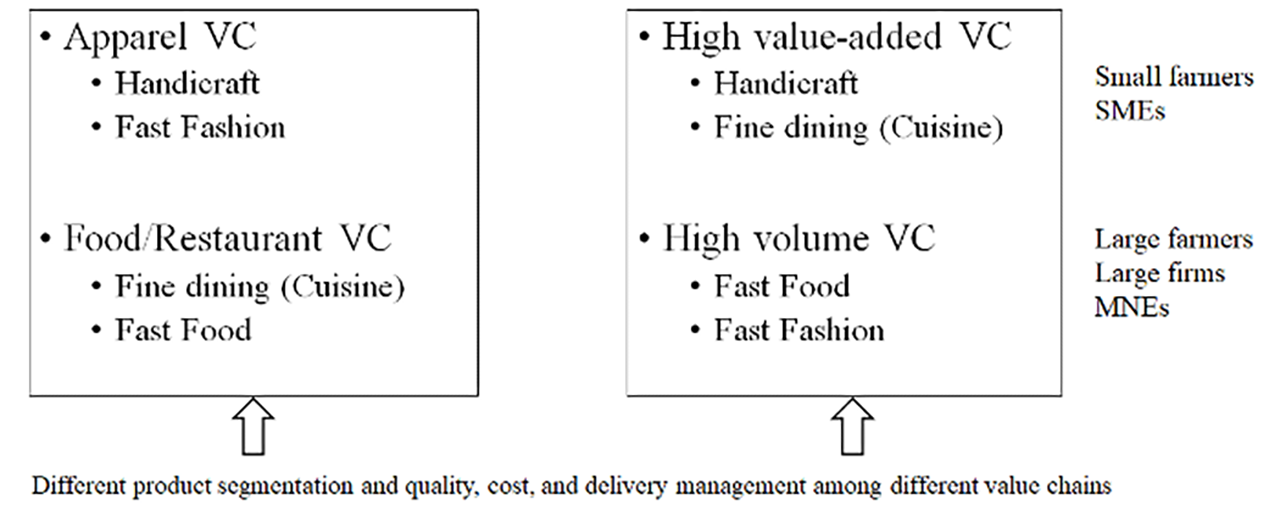

- Policy RecommendationsⅧ Diversity in agricultural value chains toward developing inclusive sustainable agricultural systemFrom commodities to crafts: Diversity in agricultural value chains toward developing inclusive sustainable agricultural system

- Policy RecommendationsⅨ Health Care and Medical Care

- [Special Article 3] Building a Well-Being Civilization -The “Adapteering” Evolution of the Modern Civilization

- Profiles

1. Outline

Musashino University International Research Institute has been conducting the Global South Study Group since May 2024. Discussions were held on a new global development strategy led by the Global South countries that will replace the Washington Consensus and future prospects for global governance. A report summarizing the outcomes of discussions on new trade and investment, industrial policy, energy, environment, agriculture, and health from the perspective of the Global South was prepared, published and adopted at the T20 (Think Tank 20) Summit to be held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and at the side events of the Group of 20 Summit.

2. Outline of the workshop

・From the viewpoint of development economics and development strategy, experts with first-class achievements and expertise on each major issue are invited as members of the study group. More than 50 participants from major organizations and companies in industry, government, and academia participate in active discussions both online and in person.

・As a result of the participation of the participating organizations, the participation was obtained from the section chief and assistant level of ministries and agencies (Cabinet Secretariat, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, MHLW, MAFF, METI, the Ministry of the Environment), governmental organizations (JICA, JETRO, JOGMEC, etc.), and enterprises (Keidanren and companies in the automobile, trading, energy, and land transportation sectors). (Note: From METI, the Asia and Oceania Division, the Africa Division, the Latin America and Caribbean Division, and the Financial Cooperation Division participated.)

3. Background of the Report

・The rise of the Global South is recognized as bringing about structural changes in the international community since the end of the Cold War. The Washington Consensus, announced in 1989, was drawn up as a principle that would carry through the global development trend after the end of the Cold War, a period of change in the international regime since World War II, and in the face of structural change in which former Soviet republics, mainly in Eastern Europe, newly entered the “West.”

・Following the global financial crisis (GFC: also known in Japan as the Lehman shock), the Group of 20 Summit was established, and it has been recognized that the traditional Group of 7 cannot manage the global economy alone. However, the Washington Consensus and the Western-led global economy based on it still have enormous influence.

・In the 20 century, some Asian/African countries were regarded as recipients of development assistance from developed countries, but in the 21 century, they emerged as the “Global South” and began to gain a significant voice in the international community. In line with the rise of the BRICS, the establishment of an international regime that supports the voice of the Global South, such as the expansion of the BRICS, is proceeding.

・Against this background, Musashino University (MIGA-GSRC) has compiled a Policy Proposal on Diversity Pathways for “No One Left Behind” (hereinafter MIGA-PP) that accurately assesses the impact of the rise of the Global South on international politics and economics and provides a basic direction for the development of international society after the rise of the Global South. In other words, this document is not a proposal that calls for small-scale improvements only in the economic field, but is intended to point everyone living in the global community to the basic direction of how the international community will operate in the future.

4. Summary of the Report

・The essence of a “manifesto” as an idea for development and development is to show “simplicity of understanding.” The Washington Consensus after the end of the Cold War was easily accepted because it was intended that the development of democracy, coupled with the transition to a market economy, would promote regulatory reform and lead to economic development.

・On the other hand, the basic issue of this study group is that there is a possibility of realizing sustainable development of the Global South countries in the future by exerting their own abilities and creativity, rather than simply following the path taken by the developed countries of Europe and America (traditional developed country path).

・In particular, until the middle of the 20 century, the dominant concept was that modernization (economic development) would be achieved through development assistance and support from developed countries in Europe and America. In other words, development strategies were considered to be exogenously given (achievable with assistance and guidance from developed countries). Therefore, the major international regimes established during the 20 century (such as the United Nations) encouraged the deployment of various forms of development assistance from developed to developing countries based on the above perspective.

・In the 21 century, new developments in the international community forced a gradual revision of this idea. The first is China’s rapid economic development. While the economic development of developed countries in Europe and the United States has slowed down due to the Lehman shock, the development of emerging countries called BRICS has been showing rapid development, including a system different from democratization and market economy. (* In order to understand these phenomena, comparative political economics between authoritarian and democratic countries has become popular mainly in Europe and America.)

・The essence of today’s global south debate is that many developing countries, not only China and some BRICS countries, are showing their own rapid economic development. The countries of the Global South are now able to take their own development strategies endogenously, based on their own ingenuity, while referring to the examples of developed countries.

・Leapfrog economic development is one way of doing this. Unlike developed countries that experienced digitalization based on the development of the manufacturing industry (heavy chemical industry), Asian and African countries have seen cases of rapid development of the digital services industry taking advantage of the rapid spread and development of communication equipment.

・In this way, we will try to formulate an argument based on the premise that “diverse paths” exist for the development of the countries of the Global South, unlike those followed by developed countries. While the ultimate goal of modernization (economic development) is shared (we call it “Global Common Targets”), the diversification of methodologies to reach this goal is reconsidered. This concept is also compatible with the “Common but differentiated responsibilities (Common But Different Responsibilities: CBDR)” in climate change countermeasures and the “Various Pathways to Decarbonization” in energy policy. (* As energy policies and the spread of next-generation vehicles are diverse, it is easy to understand that economic development strategies based on these policies are also diverse based on national circumstances.)

・As shown in the following sections, a total of nine policy proposals were made on the “diversity pathways” that should be in the fields of industrial policy, digital, energy and environment, finance, agriculture, and health and hygiene in the following formats.

① The Global Common Target is a set of global common goals agreed upon by both the developed countries and the Global South.

② In order to realize the “Global Common Target,” the “Traditional Developed Country Pathways” are the methodologies that have been implemented by developed countries in the past and that are strongly encouraged to be adopted by developed countries in the Global South today.

③ In response to this, the Global South proposed a methodology that could be independently promoted by its own ingenuity as the Global South Diversity Path.

④ In addition, the necessary policy measures to realize the “Global South Diversity Path” are summarized.

5. Future Activities and Major Schedules

・11 March 13, 2024 Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Inonovation Strategies for Disaster Resilience: Fortifying Global South Economies Through Dynamic Governance Solutions attended the T 20 Summit and the side events of the Group of 20 Summit. Publication, submission and adoption of the Report. (* Participation in the conference was an invitation from the Brazilian Presidency and was not supported by the Government of Japan.). In addition, on the 14th, he was invited to the G20 Social Summit, which was established by the Brazilian President this year, and discussed the same theme for 2 hours. It should be noted that this event was hosted by Brazil, not Japan, and that we were invited to participate.

After the conclusion of the 2024’s Group of 20, the Global South Study Group will be held in preparation for 2025’s Group of 20 and TICAD, and further concrete policy recommendations will be made.

・January 2025 T20 Contribution to South Africa’s Policy Advocates.

・TICAD held in August 2025

・Group of 20 South African Leaders Meeting, 11, 2025.

Summary and full text of each chapter of the Report

Chapter 1 MIGA Policy Package

The Path Diversity Paradigm of the Development of the Global South

・The drastic changes in the basic structure of the international community today can be summarized as the rise of the Global South. The phenomena of the rise of the Global South must be predicated on the diversity of the development path of modernization.

・The recognition of diversity in the development path of modernization suggests the possibility of endogenous modernization (economic development) of Asian/African countries.

full text

Prof. Hidetoshi NISHIMURA, President, Musashino Institute for Global Affairs

Prof. Mitsuhiro MAEDA, Musashino Institute for Global Affairs

1. the concept of the path diversity

One of the most notable phenomena in the international community today is the rise of the Global South (GS; the concept of developing countries is referred to here as the “Global South”). The GS states, which have succeeded in achieving rapid economic growth since the end of the 20th century, have begun to exert a strong political voice in the international community against the backdrop of their economic presence. The international regime up to the 20th century, which was constructed by a small number of limited developed countries, is coming to an end. In order for the international community to construct a new international regime that will exercise effective global governance in the second quarter of the 21st century and beyond, it is necessary to accurately understand the historical significance of the rise of the GS states through a deeper understanding of the views of the GS states toward the international community that they advocate.

In 1989, it was understood that the structure of the Cold War, which had been maintained for 40 years, would collapse, and the Washington Consensus, which laid out the structure of the international community after that time, centered on the development strategies of the countries in the transition economies that would newly join the “Western” developing countries, was announced. The Washington Consensus was a strong statement of neo-liberalism, which favored the market mechanism in all its aspects, since the West, with the market economic mechanism as the ideological pillar of the West, had won the Cold War.

Of course, there are fundamental doubts about the effectiveness of neoliberalism, the glorification of the market mechanism in all its forms. If we still adhere to it today, it could create a number of serious problems. However, the Washington Consensus should be justly evaluated for its effectiveness in showing the structure of the international community in the immediate future, at a time when the Cold War has ended and a great number of countries in the former planned economies have entered the category of developing countries as the transition economy states. This is a situation that should be duly appreciated. Even if it caused serious problems in the long run, the Washington Consensus was not put together in the first place as a universal prescription for the very long term, and many of those problems are beyond the scope of the project.

The current movement toward the full-scale rise of the Global South states can be seen as a major movement in the history of modern civilization, not inferior to the end of the Cold War at the end of the 1980s. Therefore, following the example of the Washington Consensus, today’s international community needs to formulate a manifesto that appropriately foresees the direction of the drastic changes in the international community that are expected to occur with the full-scale rise of the Global South states, and that outlines the basic structure of the international community after that.

With this in mind, the Musashino Institute for Global Affairs (MIGA) at Musashino University launched the Global South Research Caucus (MIGA-GSRC) in FY2024 to bring together the wisdom of not only Japan but the world to address this issue. Here are the conclusions shared by the participants of the study group.

(1) The Global South, which aims to build a new idea of international social development

We believe that the GS states are pursuing a new international regime based on the idea of development that reflects their own views, questioning the legitimacy of the developmental ideas of the developed countries that have defined the international regime to date, and jointly pursuing a new international regime based on the developmental ideas of the GS states.

Only a few developed countries played a leading role in the establishment of major international regimes in the post-World War II period, and GS states had no independent channels other than responding primarily in the context of North-South issues through the UN system. For example, in the Bretton Woods system, the representative international regime for international finance, although many countries, including today’s GS, attended the conference itself (Allied Monetary and Financial Conference (July 1944)), it was the United States that effectively led the conference. That is, at the end of the 20th century, when the GS states began to increase their national power, the major international regimes had already been established and operated by others.

This old international regime does not guarantee treatment commensurate with the increased national power of the GS in recent years. For this reason, there is a certain persuasiveness in the idea that GS, in solidarity within the international community, seek improvement within the current international regime and demand rights and interests commensurate with their own national power. In this case, the basis of GS solidarity is the “acquisition of interests commensurate with increased national power” and does not represent a new contribution to human history in terms of philosophy. The current tendency to deride the emerging GS Solidarity as a “pressure group without a philosophy” reflects this way of thinking.

However, it is not appropriate to view today’s GS states’ claims as only about specific national interests, but rather as pursuing a new idea of how to govern the international community that underlies their claims. The GS states are making great strides in their economic and political rise, while at the same time pursuing epistemic rise.

A particular international regime is constructed on the basis of a particular philosophy. There is no international regime that is not influenced by a particular philosophy and that is universally and neutrally valid at any time and in any form of international society. After World War II, a number of international regimes promoting free trade were constructed. These international regimes were established at the initiative of countries that placed high value on the promotion of free trade. In 1989, the Washington Consensus was released, setting forth the direction of development strategies for developing countries, including those in the post-Cold War transition economies. It was based on a particular philosophy that placed an extremely high degree of trust in the market mechanism of neoliberalism that swept the world at the time.

In light of these facts, it is conceivable that while the claims of today’s GS states appear to be concerned with the nature of interests derived from specific international regimes, at a deeper level they are actually questioning the legitimacy today of the specific ideas upon which these international regimes are based. In fact, it may be that deep down, these international regimes may be questioning the legitimacy of the specific ideas on which they stand today.

(2) A Comprehensive Global Common Target, through Path Diversity

When considering the construction of a new international regime that reflects the developmental ideas of the GS states, the 20th century idea that a particular ideology will construct the international regime will lead to a new conflict, such as choosing between the ideas of the developed countries and those of the GS states. We must break away from this 20th century thinking, and instead of asking which particular ideology should take hegemony, we must first build a consensus on a global common goal (we call this the “Global Common Target”) that is shared by all countries that make up the international community, without dividing the developed countries and the GS states. We have come to the conclusion that we need to build a consensus on the Global Common Targets, recognize the diversity of pathways to reach them, and establish a concept of comprehensive support and cooperation from the viewpoint of global development, with each country taking the most appropriate measures. We call this concept of multisystemic nature “path diversity.”

Global Common Targets are not a new concept. In today’s global society, there are already common goals (Global Common Targets) shared by all countries, both developing and developed countries. Typical examples are the 17 goals listed in the SDGs, the reduction of greenhouse gases in the fight against global warming, and the promotion of free trade symbolized by the establishment of the WTO, etc. Some short-sighted arguments argue that GS states are questioning these common goals themselves, which were established at the strong initiative of developed countries. However, the Global Common Targets were not established by the developed countries for the purpose of domination of the entire planet by the developed countries, but were set and agreed upon by the developed countries and GS states for benefit of the entire global community, including the developed countries and GS states, after repeated discussions. The GS states have substantially participated in the establishment of the Global Common Targets, and their achievement will benefit the global community as a whole, as well as the interests of the GS states.

On the other hand, the way in which the Global Common Targets are being realized in the international community today is not without problems from the perspective of GS states. Developed countries tend to consider their own path of economic development as the best one, especially in terms of economic development paths, and to strongly urge GS states to follow it. In the process of persuasion, they have provided enormous amounts of technological and financial assistance, and it can be said that they have a sense of responsibility as a matter of civilization history to make the GS states follow the path they have taken in the past in the same form as they have. However, we believe that in many cases, this is seen by GS states as a block that greatly restricts their freedom in making policy decisions.

As mentioned earlier, GS states have actively participated in the process of setting the Global Common Targets, and if the Global Common Targets were set as a consensus of the international community as a whole, they would fully recognize or not deny the importance of compliance with the targets. However, we should not be bound by the historical paths taken by developed countries, but rather recognize the various paths that GS states can take based on their own free ideas. We believe that this kind of thinking may lie at the root of the arguments of today’s GS states.

This idea is summarized as a consensus of the Global South Research Caucus (MIGA-GSRC),

A Comprehensive Global Common Target, through Path Diversity.

(3) Beyond preconceived notions of modernization path

In today’s global society, all social systems are working toward a common goal: the promotion of modernization. Modernization is defined here as the process by which a social system is managed according to a modern system of thought, resulting in an increase in GNI per capita. The question of whether modernization is endogenous or exogeneous is thus a matter of debate. In fact, the difference of views on this issue can be seen as the source of the current ideological conflict between the GS states and the developed countries.

The prevailing view in the current international regime is that the best path to achieving the Global Common Targets is for GS states to follow the path that developed countries have taken in the past, and that it is difficult for GS states to modernize endogenously, and that they can only do so through exogenous interventions of assistance and guidance from developed countries. The traditional path is a variety of policies based on the idea that the modernization of GS states can only be done exogenously under the direction of developed countries.

In contrast, the concept of path diversity is based on the idea of broadly recognizing the potential for endogenous modernization in the GS states. The endogenous development of the GS states is indispensable for the balanced development of the developed countries on a global scale, and as equal partners in making this development possible, it is necessary to fundamentally reconsider what the developed countries have traditionally considered aid and guidance. The historical paths taken by the developed countries show the results of their endogenous modernization. If GS states promote endogenous modernization, they will not do so exogenously with the help and guidance of others, and their paths will naturally include their own. Therefore, it is only natural that the path will be different from that historically followed by the advanced countries that preceded them in time.

To summarize the discussion, the essence of the question we must consider today is the question of what phase of the evolution of modern civilization we are in today, a quarter of a century into the 21st century, from the long-term perspective of the evolution of modern civilization. It is clear that the origin of modern civilization is Western Europe, and for a long time there has been a strong negative view of the ability of the GS states to promote endogenous modernization. It is also true that the developed countries, with a strong sense of mission that their own assistance and guidance are indispensable for the modernization of the GS states, have strongly demanded that the GS states follow the same historical path that they themselves have followed. There were good reasons to justify this in each era. Today, this situation has changed, and endogenous modernization of the GS states is considered to be justified.

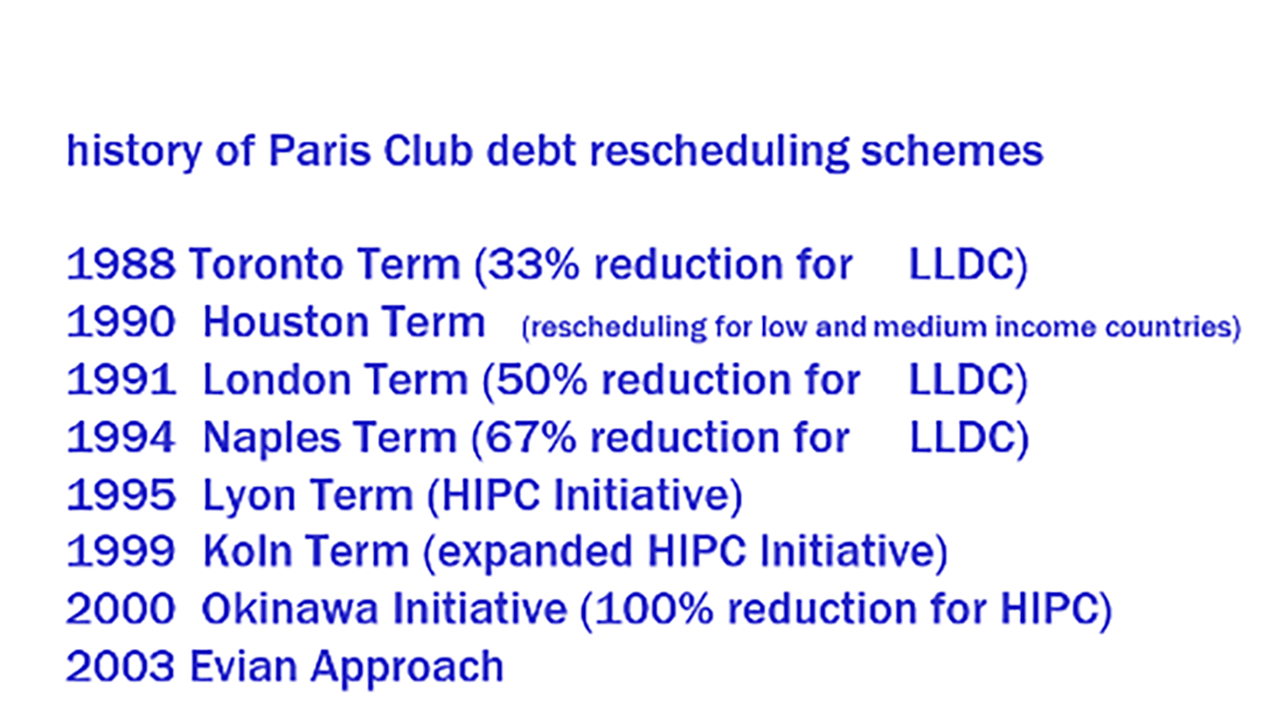

2. the current international regime of development assistance and the exogenous modernization of the Global South states

The international regime, especially international development regime, which has an important influence on the way GS modernization was constructed during the 20th century. The idea that runs through the GS is an exogenous idea of GS modernization.

Looking at the international development regimes still in operation from this perspective, there is indeed a strict distinction between developed and developing countries and between donor and recipient countries. The OECD’s DAC List of ODA Recipients, which classifies developing countries into four categories based on a single indicator, GNI per capita, can be seen as a typology of developing countries based on such a distinction.

The Washington Consensus, published in 1989 by John Williamson, a research fellow at the Institute for International Economics and an international economist, identified ten conditions as the greatest common denominator that would enable developing countries to attract investment from developed countries and achieve self-sustained economic growth. The ten conditions are: reduction of budget deficits, reduction of government spending including cutting subsidies, tax reform, interest rate liberalization, competitive exchange rates, trade liberalization, promotion of direct investment, privatization of public enterprises, deregulation and establishment of property rights laws. This is simply the “developed countries’ idea” of the GS development path proposed to the countries of the Global South from the side of the developed countries.

The Millenium Development Goals (MDGs), the predecessor to the current SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals), can also be seen as based on this sharp distinction. The MDGs emphasized focused aid to sub-Saharan Africa, a region that is typical of developing countries that have not yet begun to modernize, with grant in the social sector as the main modalities of aid.

3. Changing Phases of the International Community

It is true that during the 20th century, the international regime based on a structure that strictly distinguished developed countries from developing countries, as described above, was highly effective in many situations, although it contained many problems. However, we believe that the following changes in particular have had an important impact on the effectiveness of the international development regime, and as a result, the structure of distinction that once functioned effectively may be becoming meaningless today.

(1) Changes in the international development finance environment

Today’s international community continues to face a major challenge that it shares with the 20th century. It is the need to build vast infrastructures in the developing world that will drive new modernization. Without invoking the Solow-Swan model of growth accounting, infrastructure construction is one of the greatest drivers of economic growth in developing countries. Without infrastructure construction, there can be no economic growth.

The biggest problem in infrastructure construction is financing.

Infrastructure, by definition, faces a market failure, so it cannot proceed if it is left to private companies in the marketplace; it must be financed with “public support” by the government. While some governments have established their own “official supported” financing schemes for infrastructure construction within their own countries, as was the case with Japan’s FILP(Fiscal Investment and Loan Program) system after World War II, they are in the minority. The overwhelming majority of developing countries are unable to obtain a sufficient amount of financing within their own governments and turn to foreign countries and international organizations for assistance. In response to these requests, developed countries and international organizations provide “official supported” financing to developing countries for infrastructure construction, known as international development finance.

Comparing the international society of the 20th century with that of the 21st century, we can see that the international development finance environment has changed drastically. Therefore, in order to achieve the goal of promoting the smooth modernization of the entire world, including the GS, it will be necessary to provide developing countries with appropriate financing for infrastructure construction based on the premise of this drastically changed international development finance environment.

In the 20th century, an extremely sophisticated system was established for financing infrastructure construction provided by developed countries and international organizations to developing countries. The question is whether the 20th century system can still function effectively in the 21st century, when the international development finance environment has changed dramatically. If its effectiveness is in question, we must build a new system of finance.

We can summarize the changes in the international development finance environment in the 21st century as three convergences.

The first is that the distinction between donors and recipients, between developed and developing countries, which was clear during the 20th century, is losing its significance, as evidenced by the functioning of the OECD’s DAC list.

In the 21st century, not only China but also the BRICS countries and some G20 countries have emerged as developing countries that accept ODA funds from donors and at the same time provide large amounts of development assistance funds to many developing countries as donors themselves. It is no longer realistic to divide the world’s countries into two categories: donors (≒developed countries) and recipients (≒developing countries). The share of countries that maintain their status as developing countries but have become major donors themselves is rising rapidly in the global flow of international development finance.

According to OECD-CRS (Common Reporting Standard) data, China has already far surpassed Japan, the largest contributor among the G7 countries, in terms of cumulative bilateral official loans (commitment basis) to developing countries from 2010 to 2021. India and Saudi Arabia have also surpassed all G7 countries except Japan, France, and Germany. The scheme in which developed countries provide development assistance funds and developing countries receive development assistance funds has already collapsed.

We call this loss of significance of the distinction between developed and developing countries the first convergence.

The second is the loss of significance of the distinction between commercial and officially supported financing.

During the 20th century, there was a clear distinction between the role of government and the role of the private sector in infrastructure construction. Infrastructure is by definition a project that faces a market failure (the amount of supply in market equilibrium is significantly less than the socially optimal amount of supply). Therefore, as a project, there will always be sectors of the project that lose money. The basic idea of the 20th century was to limit the role of the government strictly to this market failure or deficit sector, and leave the commercially viable sector to the private sector. In this case, since the government was to promote projects that would incur a deficit, “officially supported” financing was used to finance them, and if it could not finance them within its own borders, it would rely on development assistance from developed countries. International development finance was provided by developed countries to developing countries in response to such requests.

In the 21st century, however, it has become common for infrastructure projects to be carried out in a mixed manner, without a strict distinction between the deficit and commercially viable sectors, and accordingly, new financial techniques such as project (non-sovereign) finance, securitization, and Land Value Capture (LVC) have been widely used. As a result, it is no longer practical today to tie a particular project to a particular modality of finance, and each project is financed through a mixture of many different modalities.

We call this loss of significance of the distinction between commercial and officially supported financing the second convergence.

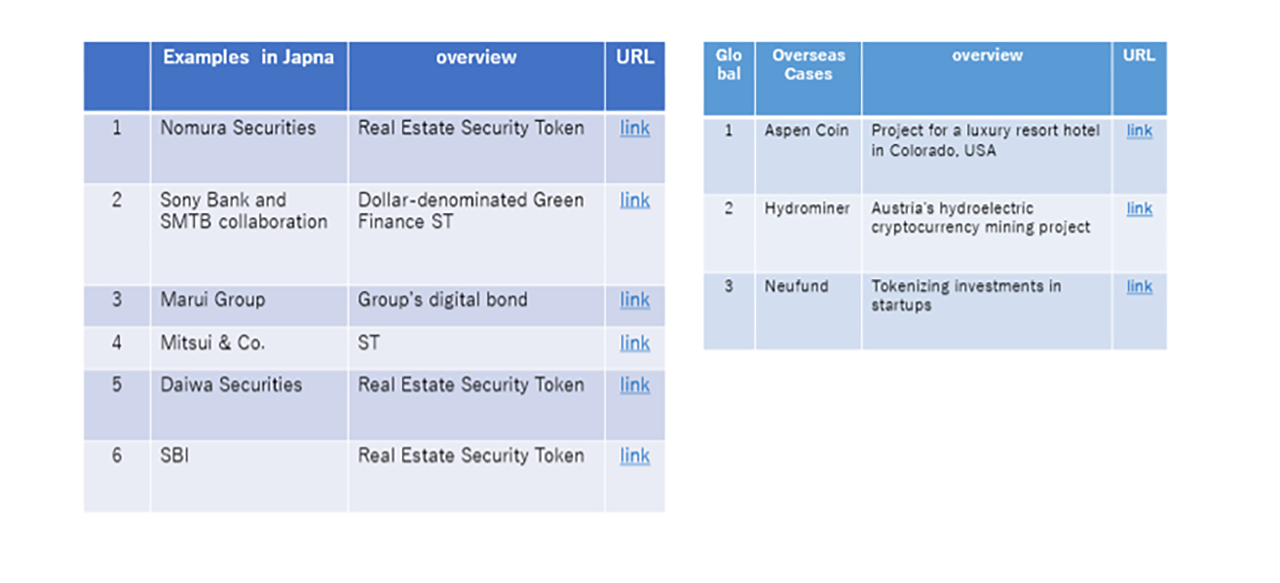

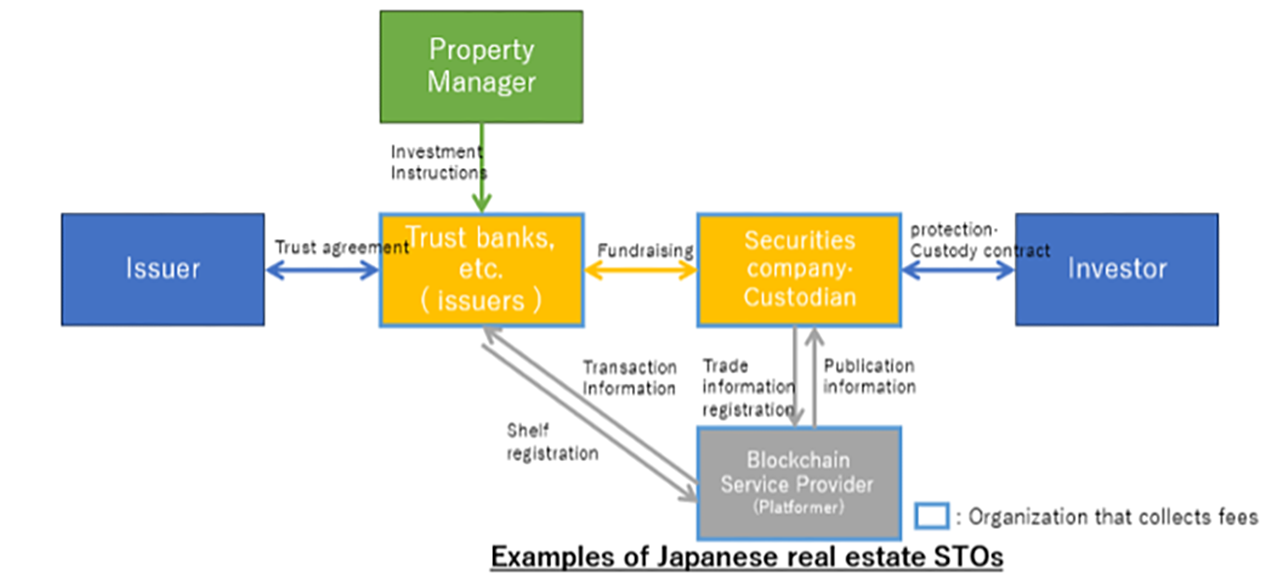

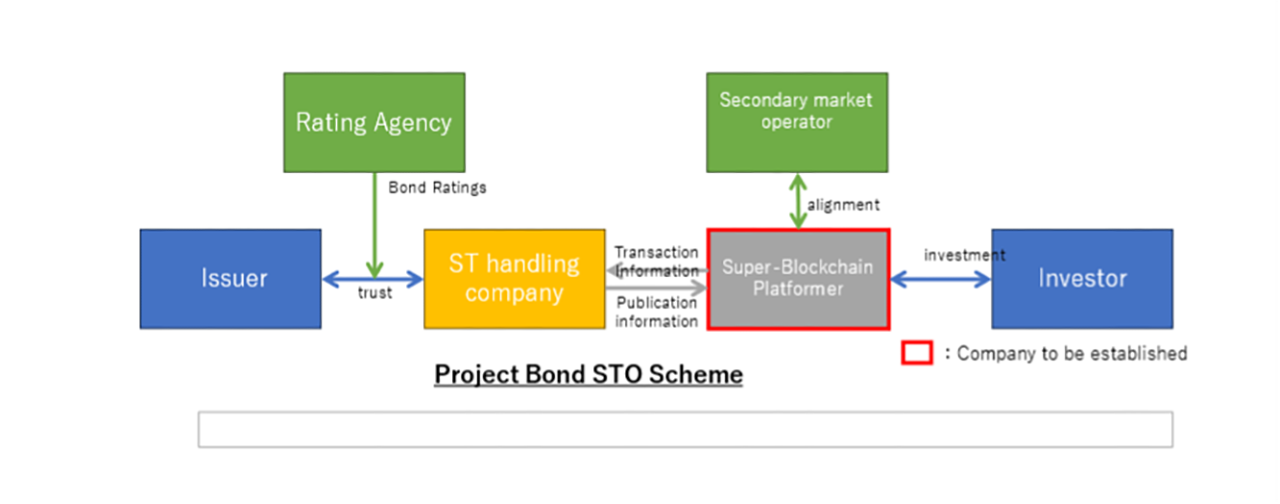

Third, while corporate finance was the dominant form of financing in the 20th century, direct financing through securitization has expanded in the 21st century, and project finance, which does not require a corporate guarantee, has become more common. The era of corporate finance-centered approach in finance practice has come to an end, and various financing methods such as direct finance, project finance, and blockchain-based sto (security token offering) have become available, allowing the selection of the most appropriate financing method for each situation. We call this the third convergence.

At a time when corporate finance was virtually the only financing option available, finance practitioners only needed to assess the creditworthiness of the lender’s corporate entity. Various rating agencies had already evaluated the creditworthiness of the corporate entity, and the creditworthiness of the corporate entity could be largely referenced by the various rating agencies. Furthermore, since the creditworthiness of a corporation is backed by collateral, finance practitioners could operate a sound financial business by focusing on the collection of collateral. In other words, finance practitioners were able to conduct financial business without having much knowledge of the financial system itself.

(2) Changing in Major Forms of States (nation building)

While nation-states were the dominant forms of nation building in the international community in the 20th century, in the international community since the latter half of the 20th century, integrated states, regional communities, and FTAs, which are different from nation-states, have come to play an important role. These are entities that have a structure that incorporates entities other than the traditional single nation-state, and that have come to play an important global governance function in the international community.

The first “integration” is horizontal integration, i.e., the bringing together of several nation-states.

Its representative is, needless to say, the European Union (EU). This was the result of the Schuman Declaration of 1950, which was inaugurated on November 1, 1992.

On the other hand, even though the success of the European Union is certainly noteworthy in the history of modern civilization, the EU is not the only way to build an integrated state.

ASEAN, established by the Bangkok Declaration in 1967, initially had strong achievements as an anti-communist political coalition during the Cold War era, but it transcended the North-South problematic approach and actively promoted market integration policies since 1992, accelerating its growth after each of the many economic crises it has overcome, and by the end of 2015, the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) was launched, creating a market-integrated development mechanism of its own. In the process, ASEAN has started to host important forums that deal with many issues in the Asia-Pacific region under the idea of ASEAN Centrality, such as starting the ARF (ASEAN Regional Forum) in 1994 and the EAS (East Asia Summit) in 2005, and today ASEAN can be seen as one of the key actors of global governance in the international community. In addition to the Economic and Social Community and the Political and Security Community, ASEAN has also made cultural diversity among its member states a pillar of its growth and development, as seen in its promotion of the Socio-Cultural Community.

Similar developments are also being seen in the African continent. In the African continent, the regional organization covering the entire continent is the African Union (AU), which was established in 2002 as an outgrowth of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) established in 1963. It has 55 member states.

There are many challenges that must be overcome before the African continent as a whole can become a single integrated state based on the African Union, and the outlook is not optimistic. In contrast, eight Regional Economic Communities (RECs) have been established under the African Union, and some of them have already achieved a high level of integration. The potential for a uniquely African style of integrated state can be discerned in these RECs, which differ from the European model of the EU and the Southeast Asian model of ASEAN.

For example, ECOWAS: Economic Community of West African States has established a system in which the decisions of the regional economic community have a strong influence on the national legislation of member countries. In the Southern African Development Community (SADC), regional cooperation among development banks has been greatly enhanced through the Development Finance Resource Center (dfrc), an organization established within SADC to coordinate the development banks of member countries. Regional collaboration among banks is making great progress.

Furthermore, although different from regional organizations, the movement to establish FTAs, which is being vigorously pursued in various regions in the 21st century, is also considered as a way to realize diverse trade, investment, and other forms of governance, as opposed to the uniform governance under the WTO.

Although the RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership), the world’s largest regional economic partnership framework, was initially discussed only in the economic sectors related to FTAs, the 10-year process of consensus building among member countries has resulted in the establishment of a sophisticated institution.

In South America, it is represented by the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), even though a number of countries have had their status suspended since its establishment by the leaders of 12 countries in 2004. This is officially a South American intergovernmental organization formed in 2007 with the goal of “same currency, same passport, one parliament,” and is intended to be a European Union (EU)-style political union.

On the economic front, Mercosur, established by the 1991 Asunción Treaty and the 1994 Ouro Preto Protocol, has made important progress toward the creation of a free trade zone in South America.

Another historical example is the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC: United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean), which was established in 1948 as one of the regional economic commissions of the United Nations Economic and Social Council. It is characterized by a very large number of member countries (46).

Of course, it is not realistic to expect that all of them will become more cohesive and emerge in the international community as global governance actors on par with the EU and ASEAN. However, their emergence does indicate the expansion of path diversity efforts in the 21st century.

The second type of “integration” is vertical integration, i.e., the participation of entities that were considered private citizens in the nation-state and were not involved in the governance functions performed by the government in the governance mechanism of the social system. In this mechanism, the private sector is to take charge of the social system in cooperation with the government. The opportunity for this is the emergence of global platform players.

Technologically, global platform technologies are now capable of performing governance functions of social systems that were previously handled solely by the state governments at an overwhelmingly low cost. On the other hand, whether or not to actually incorporate them into the governance mechanisms of the social system is a complex political decision, and it is difficult to foresee the direction of this decision at this point in time.

(3) Transition of the Leading Industries

The status of the leading industries that support the world economy has changed dramatically between the middle of the 20th century and the 21st century.

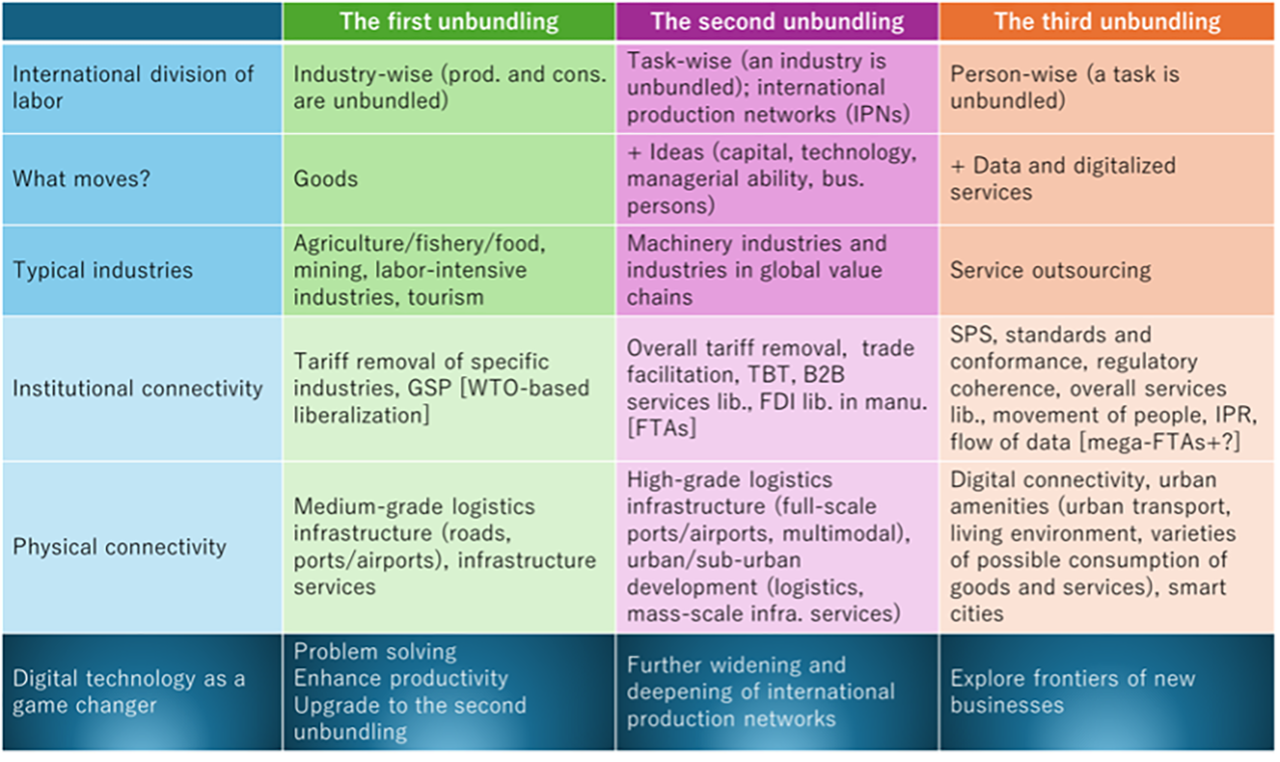

The transition of the leading industries can be viewed from the perspective of the nature of the international economic division of labor as a transition of three phases, as shown in the following chart. The basic concept is unbundling, which can be summarized as follows. The unbundling concept described here is based on Richard Baldwin [2016] (Richard Baldwin “The Great Convergence”, Harvard University Press, 2016). 2016), developed on the basis of ERIA [2022] ( Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA). (2022) The Comprehensive Asia Development Plan 3.0 (CADP 3.0): Towards an Integrated, Innovative, Inclusive, and Sustainable Economy. Drafted by Fukunari Kimura and ERIA team).

The first phase is called first unbundling, the unbundling of production and consumption. This movement is said to have taken place since the 1820s.

The second phase is called second unbundling, which refers to the international division of labor on a task-by-task basis, thus creating the International Production Network (IPN). This is a movement that has been taking place since the 1990s.

The third phase is called third unbundling, which refers to an individual-by-individual international division of labor that is established by unbundling tasks. This is a movement that has been underway since the 2015s.

These phase transitions will significantly change the status of the leading industries.

What moves in First Unbundling are goods, and the main industries that will develop the international division of labor in this phase are agriculture/fisheries/food, mining, labor-intensive industries, tourism, etc. The institutional connectivity to develop the international division of labor in this phase will be WTO-based liberalization, such as the elimination of tariffs on specific industries and the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP). In addition, intermediate logistics infrastructure (roads, ports, and airports) and infrastructure services will be important as physical connectivity to develop the international division of labor in this phase.

What moves in Second Unbundling are ideas (capital, technology, management competency, business people) in addition to goods. Main industries that will develop the international division of labor in this phase are machinery industries and industries based on the global value chain. The institutional connectivity to develop the international division of labor in this phase will be FTA-based liberalization, including general tariff elimination, trade facilitation, technical barriers to trade (TBT), B2B services liberalization, and liberalization of foreign direct investment in the manufacturing sector. In addition, as physical connectivity to develop the international division of labor in this phase, advanced logistics infrastructure (full-scale ports/airports, multi-modal) and urban/suburban development (logistics, large-scale infrastructure services) will be important.

What moves in Third Unbundling are data, in addition to goods and ideas. Main industries that will develop the international division of labor in this phase are services, outsourcing, and other industries. Institutional connectivity to develop the international division of labor in this phase will include sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS), standards and conformity, regulatory consistency, overall service liberalization, movement of people, intellectual property rights, data distribution, and other mega-FTA-based liberalization. In addition, the physical side of the response (physical connectivity) to develop the international division of labor in this phase will be digital connectivity, urban amenities (urban transportation, living environment, and the potential for consumption of various goods and services), and smart cities. And as disruptive technological innovation progresses, the level of massive electrical energy consumption demand required by the vast semiconductor-based developments of the third unbundling will be far greater than in the past, when unbundling was supported by energy produced from fossil fuels. The core of this demand is the distribution of huge amounts of data, which requires far more energy than unbundling was once supported by energy produced from fossil fuels, and the energy problems required to overcome them must now be realistically addressed in the context of global environmental issues.

[Chart 1] Three unbundling

(Source: ERIA2022, Material presented by Fukunari Kimura, member of the Global South Study Group)

4. The Path Diversity and the MIGA Consensus

(1) The idea of endogenous modernization

In light of the changes in the international community as described above, it is true that today the rationale for the former idea that exogenous modernization is optimal for GS and that the possibility of endogenous modernization is difficult to achieve is fading. The legitimacy of the structural understanding of development as the progression up the DAC ladder is also becoming questionable. The slogan of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), ‘No One Left Behind,’ is a clear illustration of this idea.

Is the era of endogenous modernization in GS countries really coming to an end?

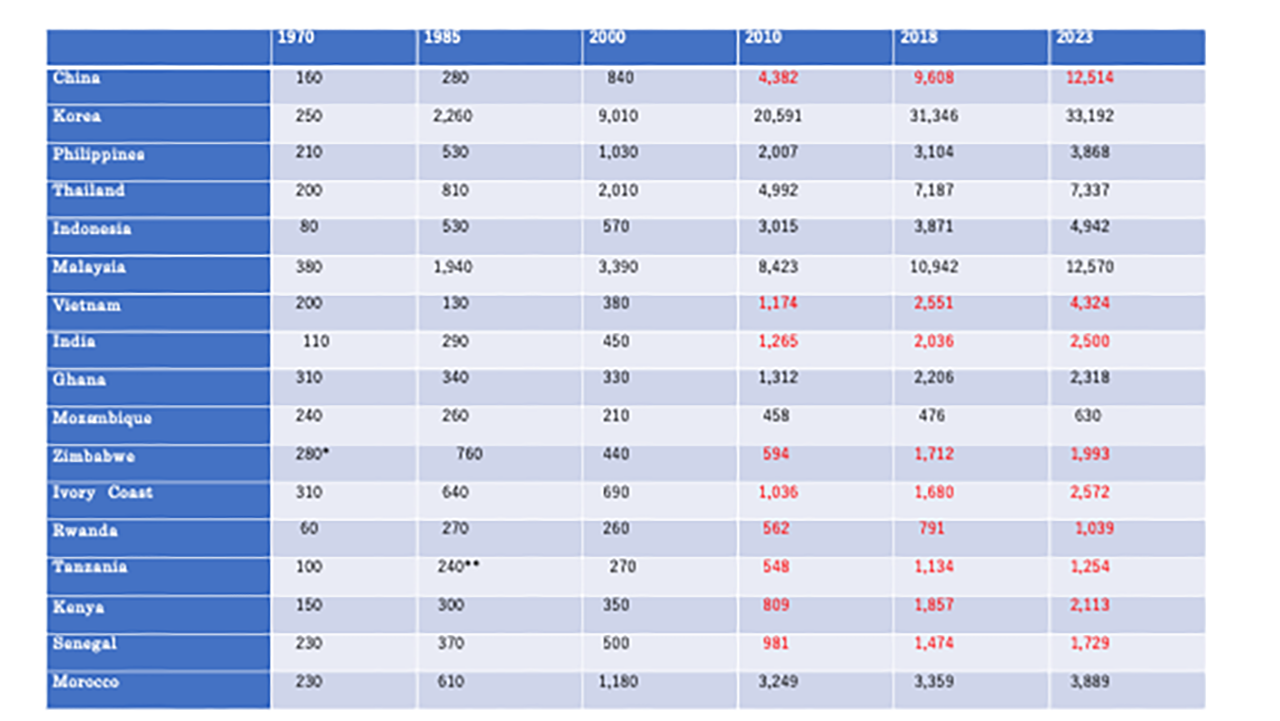

To consider this, it is useful to look at the per capita GDP of each country.

[Chart 2] GNI per capita in Asian and African countries

(Source: the author based on World Bank Atlas (World Economic Outlook for 2010, 2018, and 2023).

It is clear that there is a clear difference between the 20th century and the 21st century: during the 20th century, the economic growth of East Asia was remarkable, while Africa remained stagnant. Therefore, among developing countries, East Asian countries were considered “superior” and African countries were considered “inferior”.

A notable trend in the 21st century is the rapid economic growth of African countries, which is believed to be due to the fact that African countries were not keen on adhering to the Washington Consensus during the 20th century, but began to adhere to it in the 21st century.

However, in the 21st century, when the international community is undergoing the changes described in section 3, it is not reasonable for the international community to leave the acquisition of wisdom on how to promote endogenous modernization to the developed countries, and for other regions to maintain a system in which they practice the guidance of the developed countries in terms of wisdom. The international community is not considered to be rational to maintain a system in which the rest of the world is left to the developed countries to practice their guidance in wisdom.

Of course, the content of modern civilization is profound and complex. There is little reason to believe that only modern civilization is overwhelmingly superior to all the wisdom that has been accumulated since the beginning of the history of human civilization, or that it is overwhelming in quantity. In particular, today, there are many problems, including global environmental issues, that can be attributed to the systemic risk of the basic framework of modern civilization. In this context, the validity of strategies that continue in the 21st century to be based on the supremacy of wisdom constructed in accordance with the framework conceived by Western Europeans is considered to be shaky.

In the 21st century, Asia/Africa is achieving economic growth through modernization in a sufficiently sustainable manner, each in its own way. While it is of course fair to acknowledge that the wisdom of Western Europeans has played an important role in the success of the region today, it is also legitimate to recognize that the wisdom traditionally nurtured in Asia/Africa has also made a considerable contribution, which will be even more necessary for the future development of the world.

In the 20th century, developing countries could not raise the necessary funds for infrastructure construction on their own and had to rely on the support of developed countries and international organizations. In the 21st century, it is now possible to greatly reduce the ratio of projects that rely on support from developed countries and international organizations, depending on how the project is structured. Under such circumstances, if developed countries continue to try to lead developing countries as the forerunners of modern civilization with a “20th century perspective,” developing countries will have the option to shun such financing from developed countries and consider other sources, such as private finance and developing countries with an increasing donor presence.

In view of the above, the role of developed countries in the 21st century is to build a platform that will enable them to make the best use of the wisdom traditionally inherited in Asia/Africa to overcome the systemic risks of modern civilization, and to promote serious discussions on the wisdom that will save the world in the 21st century, not as a leader with “the 20th century’s gaze” but as a partner on this platform.

Some of the systemic risks posed by modern civilization may be difficult to solve effectively with only the wisdom of Western Europeans. Therefore, in order to solve them, we must consider the global integration of wisdoms, utilizing the wisdom that has been nurtured uniquely and traditionally in the Asian/African region.

On the other hand, the problem is complicated by the fact that Asia/Africa, where traditional wisdom has been nurtured, are also part of the modern civilization, which has technological progress and globalization as its inherent nature. Therefore, what is required is not to view the framework of modern civilization originating in Western Europe and the traditional wisdom of Asia/Africa as exclusive, but to take a complementary perspective in the context of the great movement of technological progress and globalization that pervades modern civilization.

(2) the MIGA Policy Package

In light of the above changes in the status of the international community today, we present the MIGA Consensus as a set of policy packages to guide the smooth economic growth of the countries of the Global South in the 21st century.

The idea that runs through the MIGA Policy Package is the path diversity to achieve the Global Common Targets based on the endogenous modernization of the Global South states.

In the most recent international community, there have been several policy packages that have been presented as providing comprehensive guidelines for the Global South. Typical of these is the Washington Consensus mentioned above, illustrating ten requirements that would allow them to maintain debt sustainability and economic growth. If each of these ten requirements is evaluated as an economic policy that promotes economic growth, they are all appropriate. On the other hand, if the Washington Consensus is taken as a comprehensive guideline for economic growth in the GS states, a fundamental problem arises. The reason is that the Washington Consensus does not envision almost all GS states promoting modernization simultaneously in the mid-21st century. In 1989, at the end of the Cold War, it was assumed that very few GS states would be able to adequately do the requirements set forth in the Washington Consensus.

As the number of GS states who have done their requirements as indicated in the Washington Consensus has increased dramatically, and we have entered what we call the Third New Modern Era, an era in which virtually all countries on the planet are steadily promoting economic growth, global-scale problems that we might call the systemic risks of modern civilization, such as global environmental problems, unacceptable uneven distribution of wealth, the emergence of a digital divide, and the construction of a huge consumption system led by the developed countries of electric energy, have begun to emerge. Naturally, no solution to these systemic risks of modern civilization can be found in the Washington Consensus.

The MIGA Policy Package is based on this background and includes a policy package that is a reference for economic development that will appropriately respond to the needs of the GS states today, while fully taking into account the systemic risks of modern civilization. In a sense, it is a reorganization of the Washington Consensus from the perspective of the GS states at the end of the first quarter of the 21st century.

The perspective of the GS states that is missing from the Washington Consensus but will be included in the MIGA Policy Package is the idea of the endogenous modernization capacity of the GS states and the path diversity to achieve the Global Common Targets based on that capacity.

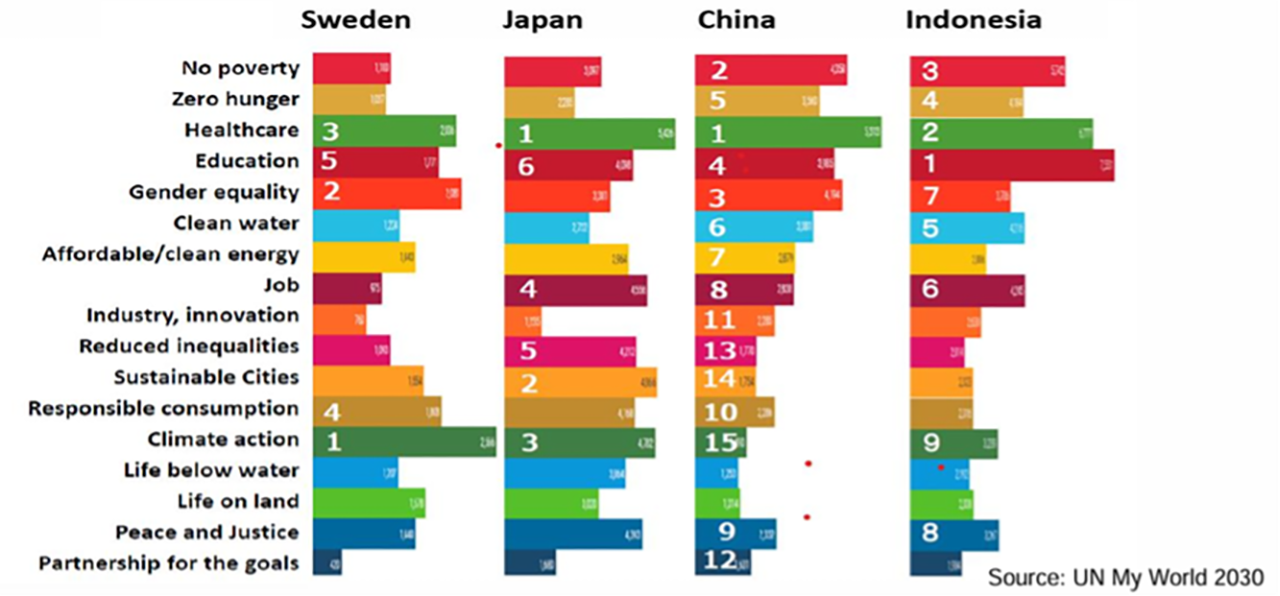

The areas covered by the MIGA Policy Package are in accordance with the SDGs.

The 17 major goals of the SDGs can be summarized into four areas in terms of content. The first area is related to the social sector. Specifically, Goal 1 is “poverty,” Goal 2 is “food security,” Goal 3 is “healthy lives,” Goal 4 is “education,” and Goal 6 is “water and sanitation. The second area is related to the economic sector, specifically Goal 7, “energy,” Goal 8, “economic growth,” and Goal 9, “industrialization. The third area is global environmental issues, specifically Goal 11 “cities,” Goal 12 “consumption and production,” Goal 13 “climate change,” Goal 14 “oceans,” and Goal 15 “biodiversity. The fourth area is social justice, specifically Goal 10 “inequality,” Goal 16 “justice,” and Goal 17 “global partnership.

While the MIGA Policy Package will cover similar areas, disaster reduction and social resilience in particular will be identified as core themes, and policies that contribute to both themes will be proposed based on a common format.

A common format is as follows.

The first is the content of the Global Common Targets, which the GS states participated in setting and which today the international community as a whole must unite to achieve.

Second, the Traditional Western Led Path is a path that has been proposed by developed countries to the GS states as a way to achieve their goals, is based on the historical path that developed countries have followed, and is now strongly recommended for the GS states to follow. If GS states decide that it is appropriate for them to follow this lenear path, developed countries and the GS states will work together to achieve the Global Common Targets based on this lenear path. In our terminology, this would be a lenear modernization model.

Third, a possible path for the GS states to achieve its own Global Common Targets, if the endogenous modernization potential of the GS states is broadly recognized. We refer to this as the Diversified Global South Path. If developed countries do not inhibit the GS states from pursuing such unique paths, but fully recognize the value of these unique paths, the global community will follow a multisystemic model of modernization.

Fourth, we will lay out the content of the policy responses that are necessary for the GS states to follow such a diversity path.

[Special Article 1] International Trade Order

・With regard to the global trade regime, for many emerging countries of the Global South, compliance with international rules, particularly those of the WTO, can be a catalyst for economic development in the region.

full text

Prof. Dr. Fukunari KIMURA, President, Institute of Developing Economies, JETRO

1. Weakening of the rule-based international trade order under ongoing globalization

Globalization since the 19th century has always been led by technological progress. It has increased the mobility of goods, services, capital, human resources, technology, and ideas across national borders and enabled a new types of international division of labor. Especially since the 1990s, globalization has presented emerging and developing countries with a new model of development, and has realized a great convergence of income level between North and South through the task-based international division of labor (the second unbundling) (Baldwin 2016). The rules-based international trade order built around the GATT/WTO over the 70-plus years since World War II has remained an indispensable institutional infrastructure for countries seeking to actively use globalization to generate economic growth.

Now, as geopolitical tensions, especially between the U.S. and China, deepen, the very foundations of this relationship are being shaken. As the U.S.-China or East-West confrontation deepens, a significant portion of the various policy initiatives from both sides are in violation of WTO commitments or traditional trade policy norms. The Appellate Body, the second tier of WTO dispute settlement (dispute settlement), has ceased to function, as the United States has blocked the appointment and reappointment of its members. As of the end of 2023, there were 24 cases of “appeals into void,” in which one of the countries that disagrees with the decision of the first tier panel appeals to the suspended Appellate Body. The number of cases brought to the WTO itself has been declining to a single digit per year since 2020. The loosening of policy discipline is not limited to the U.S. and China or countries belonging to the East and West, but is also extending to emerging and developing countries in the Global South, a situation that raises concerns about the weakening of the rules-based international trade order.

2. Importance of a rule-based international trade order

In globalization led by technological progress, new tipes of international division of labor became technologically possible, starting with the industrial term, then the task term, and finally the individual term. Around 1990, however, the first ICT revolution enabled the international division of labor in task units term (the second unbundling), which connected the technologies of developed countries and labor in developing countries, and the income gap between countries, especially between North and South, began to narrow. Incidentally, with regard to income inequality within each country, there are countries that have both widened and narrowed (Kanbur 2019).

It is important to note here that while some developing countries were able to successfully ride the second wave of unbundling, others were left behind. In particular, in the international production networks of the machinery industry, only East Asian countries including Northeast and Southeast Asia, a few countries in Central and Eastern Europe, and Mexico can be cited as examples of success (Ando, Kimura, and Yamanouchi 2022). The threshold between successful and unsuccessful countries is formed by institutional connectivity and physical connectivity.

The second unbundling requires that the parts and intermediate goods that connect the production blocks responsible for each task can move quickly through logistics links. Physical connectivity means whether or not a quick, efficient, and reliable physical logistics infrastructure is in place. On the other hand, institutional connectivity must guarantee the liberalization of trade and investment, as well as the free movement of goods, services, capital, human resources, technology, and ideas. It has become indispensable as a guarantee of a minimum level of institutional connectivity. Further, in the context of regional economic integration, institutional linkages have been developed that extend beyond tariffs to various policy modes.

The more sophisticated forms the international division of labor takes, the more important it becomes to ensure confidence in international rules, as policy risks are reduced, along with a favorable trade and investment environment. The more actively a country seeks to take advantage of globalization for economic development, the more important it is to have a rules-based international trade order. Rules are also often good for smaller countries that tend to be swayed by the arbitrary international trade policies of larger countries. In the face of rising geopolitical tensions, many GS countries would like to remain passively or actively neutral and remain closely linked economically to both East and West. To make this possible, a rules-based international trade order must be maintained as broadly as possible.

3. Promote the development of creative industries while maintaining international trade order.

As the confrontation between Western countries and China deepens, GS countries should be proactive in working with free trade-oriented middle powers to preserve the rules-based international trade order as broadly as possible.

Needless to say, the international trade order, centered on WTO law, is not all exemplary in light of economic theory. In addition, from the standpoint of emerging and developing countries, it is understandable that they sometimes react that the rules are imposed by developed countries, as they have not been able to actively participate in international rule-making to date. At the same time, however, the entire international trade order is being damaged by the successive disregard of international rules by Western countries and China, triggered by geopolitical tensions. The first priority should be to preserve the order as broadly as possible.

Specifically, we must first support the WTO, which has two aspects: the first is to revive its dispute settlement function. We need to work with countries around the world to resume the functions of the Appellate Body. If that does not happen soon, we would like to promote participation in the MPIA (Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement), which was started at the initiative of Europe and is intended to serve as a temporary replacement for the Appellate Body in a manner consistent with the WTO Agreement. The second is to strengthen the WTO’s ability to promote new rulemaking. While various attempts have been made, the success or failure of the joint statement initiatives (JSI) is at issue. Currently, JSIs on e-commerce are attracting attention and cooperation is being sought.

There are many other issues on which GS and free trade and investment-oriented middle powers should cooperate. For example, cooperation to reduce various policy risks can be considered. Even if it is difficult to resolve the US-China or East-West confrontation itself, we could work to clarify as much as possible the boundary between those areas that are subject to restrictions due to geopolitical tensions and those areas that are otherwise left to free trade. It would also be effective to jointly deal with the economic coercion sometimes wielded by the major powers.

Even within the framework of the existing international trade order, it is possible to implement various industrial development policies through creativity and ingenuity. While it is sometimes argued that loosening discipline and expanding policy space is desirable, it is also true that a certain degree of discipline allows reforms to be promoted by overcoming various vested interests in the country. In the larger context, it would be more beneficial for the Global South countries to maintain the existing international trade order, and a proactive response is required.

References

- Ando, Mitsuyo, Fukunari Kimura, and Kenta Yamanouchi.(2022) “East Asian Production Networks Go Beyond the Gravity Prediction.” Asian Economic Papers Asian Economic Papers , 21(2): 78-101.

- Baldwin, R. (2016) The Great Convergence: Information Technology and the New Globalization. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Kanbur, Ravi.(2019) “Inequality in a Global Perspective. “Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 15(3): 411-444.

[Special Article 2] G20-T20 Process: Can Global South Shift the World Order?

・Outline the direction of discussions led by the Global South countries in recent years (Indonesia as Chair in 2022, India as Chair in 2023, Brazil as Chair in 2024, South Africa as Chair in 2025) at the T20, which functions as policy recommendations for the Group of 20.

full text

Dr. Venkatachalam ANBUMOZHI ERIA Senior Research Fellow for Innovation

This paper highlights how the G20 as a grouping works against odds to bring forth voices from the Global South towards a post-Washington consensus on global governance while balancing the requirements of the Global North. It also highlights the focus of the G20 grouping in formulating alternate proposals under the engagement of Think Tank 20 as a knowledge partner and explains how they are slowly becoming a force to reckon with within the multilateral world.

1. Washington Consensus on Global Economic Governance, shortfalls and Emergence of G20

(1) Washington Consensus and Global South

In 1980s, the Washington Consensus evolved as a set of economic policy recommendations for developing countries in the Global South to guide their path for development based on open market principles. This often refers to the level of agreement between among the Washington based institutions namely the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, and U.S. Department of the Treasury on those policy recommendations. All shared the view, typically labeled neoliberal, that the operation of the free market and the reduction of state involvement were crucial to development in the global South. When the British economist John Williamson, who later worked for the World Bank, first used the term Washington Consensus in 1989, he claimed that he was referring to a list of reforms that he felt key players in Washington could all agree were needed in Latin America. However, much to his dismay, the term later became widely used in a pejorative way to describe the increasing harmonization of the policies recommended by those institutions. It often refers to a dogmatic belief that developing countries in the Global South should adopt market-led development strategies that will result in economic growth that will “trickle down” to the benefit of all.

The World Bank and IMF were able to promote that view throughout the developing South by attaching policy conditions, known as stabilization and structural adjustment programs, to the loans they made. In very broad terms, the Washington Consensus reflected the set of policies that became their standard package of advice attached to loans. The first stage was a set of policies designed to create economic stability by controlling inflation and reducing government budget deficits. Many developing countries, especially in Latin America, had suffered hyperinflation during the 1980s. Therefore, a monetarist approach was recommended, whereby government spending would be reduced, and interest rates would be raised to reduce the money supply. The second stage was the reform of trade and exchange-rate policies so the country could be integrated into the global economy. That involved the lifting of state restrictions on imports and exports and often included the devaluation of the currency. The final stage was to allow market forces to operate freely by removing subsidies and state controls and engaging in a program of privatization.

(2) Global Financial Crisis and Emergence of G20

By the late 1990s when the financial crisis hit Asia, it was becoming clear that the results of the Washington Consensus were far from optimal. Increasing criticism led to a change in approach that shifted the focus away from a view of development as simply economic growth and toward poverty reduction and the need for participation by both developing-country governments and civil society. That change of direction came to be known as the post-Washington Consensus which included the formation of G20.

Founded in 1999 as Finance ministers meeting and elevated to Leaders’ Summit in 2008, the G20 grouping has evolved into a distinct entity within the various multilateral forums on global economic governance prevalent today. In light of the BRICS- Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa – expansion of emerging economies that were not part of the advanced North which were party to global order setting in development finance and powerful emergence of the global South and the inclusion of African Union (AU) addition to the G20, the grouping has received more attention from policy analysts and researchers interested in finding alternate pathways for sustainable and inclusive global governance based on multilateralist principles.

As its inception began in the wake of the Asian financial crisis, the focus of the G20 has primarily been on finance. Before being elevated to the Leaders’ Summit in 2008, the G20 would only meet under the Finance Ministers and Central Bank governors to engage in discussions. The importance of the Finance Track was further solidified at the 2009 Leaders’ Summit, where G20 designated itself as the “premier forum for international economic cooperation”. The Finance Track within the G20 engages in crucial discussions taken by the Member States and the European Union. Some of the more recent successful outcomes of the Finance Track include the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), a Common Framework for Debt Treatment Beyond DSSI, the G20 Sustainable Finance Roadmap, the G20 principles for quality infrastructure investment, and a proposal to create a Financial Intermediary Fund (FIF) for pandemic Prevention, Preparedness and Response (PPR). Success in the Finance Track does not mean that other aspects of the G20, such as the Sherpa Track and the different Engagement Groups (EG), that began in 2010, did not flourish in the last 18 years. Due to the unique model of G20 being a rotating Presidency without a permanent secretariat, each member State has chosen to add its flavor to the G20. Australia’s presidency in 2014 focused on gender, with the Brisbane Leaders’ Summit Leaders endorsing the goal to reduce the gender gap in the labor workforce by 25 percent by 2025. Germany (2017), on the other hand, launched the G20 Compact with Africa during its Summit. Given the many necessities brought about by the pandemic, Italy’s (2021) Presidency centered on the Matera Declaration, referred to as “a call to action in the time of the Covid-19 pandemic and beyond.” Last year, India’s (2023) Presidency brought the focus on sustainability from a lifestyle perspective with LiFE or Lifestyle for Sustainable Development.

Some researchers have chosen to question the legitimacy of the G20 process, given its arbitrary nature and no set rules of procedure. Nevertheless, this arbitrary nature is what has worked for the G20 – the first partnership between the industrialized global north and developing economies of the global south and is the reason why it is one of the most democratic multilateral forums that many States and groupings are keen to join and pursue a global new order. Decisions in the G20 are not binding, which sometimes means that implementation of the documents may not be at par with more structured multilateral organizations such as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), or the World Trade Organization (WTO). Nevertheless, G20 meetings are followed with equal interest, if not more, and the discussions are given significant weightage in bilateral and multilateral settings.

2. New Global Consensus on Development and Evolution of Global South within G20

Because of its composition as well as agenda-setting role of the rotating presidencies, the G20 is one of the few multilateral forums on global governance that changes shape yearly. While this fact has confused many multilateral experts and made them question the legitimacy of the forum to represent the community of nations, it has worked well for this multilateral initiative. The former G8 of advance north and now G7 -the defector custodian of global governance and the prime mover of Washington Consensus – in 1999 annual Summit, which committed “to establish an informal mechanism for dialogue among systemically important countries, within the framework of the Washington Consensus, led to the selection of the G20 countries. The first ten years of the G20, from 1999 to 2008, were relatively low-key as the meetings focused on the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis. The meetings concentrated on building a more robust and healthier global financial structure. The Finance Track of the G20 found its footing during this period. Even in 2009, after the G20’s elevation to a Leaders’ Summit, the importance of the Finance Track was maintained, with the leaders terming the G20 as the “premier forum for international economic cooperation” The Sherpa Track replicated the multiple meetings of the Finance Track planned throughout the year and has now outgrown the Finance Track in the number of meetings it holds throughout the year. However, the G20 Leaders’ Summit was reduced to once a year from biannual meetings.

The Sherpa Track currently consists of 13 tracks, all of which have come into being over the years. However, this is further changing with the Brazilian Presidency, which brought in women empowerment. Traditionally, many of the tracks would be introduced first as a Task Force and then brought in as a full-fledged Working Group a year later. The Task Force would assist in setting up the Terms of Reference for the Working Group, which would determine the agenda of each meeting. Over the years, some of the Working Groups that have come about in different Presidencies are: the Development Working Group (DWG) works towards the G20 development agenda since its inception during the Republic of Korea’s Presidency (2010); the French Presidency (2011) created the Agriculture Deputies Group; the Leaders’ Declaration under the Australian Presidency (2014) led to the creation of an Employment Working Group; German Presidency (2017) established the Health Working Group; Argentina’s Presidency (2018) began the Education Working Group (EdWG); Saudi Arabia’s Presidency (2020) brought in the Tourism Working Group and the G20 Culture Ministers meeting; the Italian Presidency (2021) created the Digital Economy Working Group; and most recently, India’s G20 Presidency started the Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) Working Group in 2023.

Additionally, several initiatives were also launched by the G20 presidencies to prompt conversations among Member States. Government agencies primarily lead these initiatives. For example, the Space Economy Leaders Meeting (SELM), initiated during Saudi Arabia’s Presidency, was led by the Saudi Space Commission (2020), then by the Italian Space Agency (2021), and followed by the National Research and Innovation Agency of Indonesia (2022). India’s Space Research Organization (ISRO) followed by organizing the 4th SELM under Indian G20 Presidency. A new “initiative” of India’s G20 Presidency was the Chief Scientific Advisors Roundtable (CSAR). The G20-CSAR brings together Chief Scientific advisors of the G20 Heads of Government intending to create an effective institutional arrangement/platform to discuss global science and technology policy issues.

While the G20 has space to bring new “initiatives” or launch new Engagement Groups and Working Groups as per the current Presidency, it needs to constantly be mindful of discussions happening in other forums on topics such as education, climate and environment, and employment; for example, keeping track of developments in the International Labour Organization (ILO) for the Employment Working Group or the impact of the Transforming Education Summit (TES) on the Education Working Group.

If compared with other multilateral institutions under United Nations Systems shaping global governance, the G20 is an outlier. The mechanism of adding new Working Groups to the Sherpa Track, initiatives launched by host nations, and the non-government Engagement Groups participating and giving statements in government-to-government discussions and handing over suggestions to the leaders before their Summit meeting are not standard formats for multilateral organizations or forums.